Leonard’s Ministries, a halfway house in Chicago where he would initially reside as a stipulation of his parole. The vehicle carried Weger over the flatlands of southern and central Illinois, toward St. Wearing a dark hooded sweatshirt, Weger gingerly folded himself into the passenger seat of his niece’s gray Honda SUV. The mere glimmer of hope of this day’s arrival, he says, kept him alive, comforting him on the many dark nights alone in his cell when he doubted he’d live to see it actually come. The prospect of freedom after so long was exciting - and, for an institutionalized man such as Weger, terrifying. Weger’s family agreed they’d never seen him smile like he smiled that day. Through the years, she wrote and called and visited frequently, but she had not been allowed to embrace her brother in the 59 years he was behind bars. Pruett, who was a teenager during Weger’s trial, had bawled in court when the guilty verdict was read. Later that evening over dinner, Weger would reunite with his children, Rebecca and John, who were ages 3 and 1, respectively, when their dad was locked up. That immovable stance made the conclusion of his 24th hearing all the more stunning: a vote of 9–4 in favor of release.Īs the prison doors swung open, Weger saw his beloved younger sister, Mary Pruett, as well as her husband and two daughters, who had lobbied the Prisoner Review Board for the man they lovingly call Uncle Otto. His claim of innocence, he said, was all he had to cling to. But year after year, over the course of 23 hearings since he became eligible for parole a half-century ago, he refused.

Would he be granted parole, or would he continue to serve out a life sentence for murder in connection with one of the most notorious cases in Illinois history: the 1960 triple homicide at Starved Rock State Park? He had long been aware that the board wanted him to express remorse and that not doing so would almost certainly doom his chance of early release. Three months earlier, the Illinois Prisoner Review Board had met to decide Weger’s fate. Emphysema made breathing a struggle, and the pain of rheumatoid arthritis limited his movement. He was down to only 113 pounds, his pale scalp encircled by a faint halo of short gray hair that he no longer bothered running a comb through. But now, at the age of 80, he showed signs that he had been hobbled by time served in concrete-and-steel cages all over Illinois - at Stateville and Menard and Pontiac and Graham.

In those days he had James Dean’s swooping pompadour and svelte build, if not quite a matinee idol face.

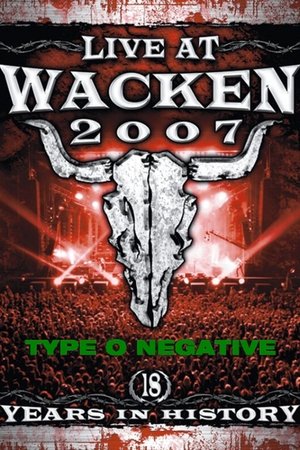

Type o negative sticker free#

When he ceased to be a free man back in 1961 and became known far and wide as the Starved Rock Killer, Weger was only 22, a chain-smoking ex-Marine, avid hunter and fisherman, and married father of two young children. It was the 21,646th day behind bars for the state’s longest-held inmate. On February 21, 2020, Chester Otto Weger, prisoner C-01114, stepped out of far-downstate Pinckneyville Correctional Center into the cool air of an overcast morning.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)